Contents:

Intricate melody is the central feature of Bulgarian instrumental music. It was traditionally played on solo melody instruments gaida (bagpipe), kaval (flute), gadulka (bowed lute) and tambura (plucked lute), sometimes accompanied by a tupan (large drum played with sticks). Harmony, introduced until the early 20th century, is a relative newcomer to Bulgarian music, although it has developed into a rich artistic environment, admitting numerous approaches. Therefore, when considering accordion bass side accompaniment, one then must make choices not only about what chords to play (a vast topic I've not yet addressed), but about the role of accompaniment in the music itself. Is the harmony there simply to support the melody or is it and end in and of itself? Since this is currently an active area of artistic endeavor, no list of such roles can be considered exhaustive. Nevertheless, several general approaches can be considered in solo accordion playing.

The "Nihilist" approach: Here you simply ignore the bass side entirely and play only melody. This is most often suggested by those unfamiliar with and, to varying degrees, uncomfortable with the accordion when looking for a way of making the accordion less noticable. This is often done under the guise of being, somehow, more "traditional". I find this approach aesthetically bankrupt, but it works for you, you're done! You can skip to the next section!

The "Drone" approach: Here you use the bass as a simple drone, in imitation of the gaida or drone-based vocal styles. While this may work occasionally for a phrase or two, it is unsuited for long passages on the accordion because bellows direction switches disturb the very quality that is most admirable in a drone: it's constancy.

The "Harmonic Tupan" approach: Here the bass provides a harmonically-flavored rolling beat under the melody, supporting it and allowing it to sing without putting itself forward into the limelight. I call this the "harmonic tupan" approach because the bass acts much like a tupan with chords. It is the main approach taken in this document, but first I should mention...

The "Orchestral" approach: Here the bass provides a fully integrated musical arrangement and harmonic context for the melody. This allows the accordion to, by itself, imitate the sound of a small orchestra. Here the bass notes cover the double-bass or tuba part and the chord buttons cover backup strings or horns. Basses are not resticted to notes in the current harmony but can also play runs or even simple versions of the melody. Single bass buttons or chords may play either with short notes or long sustains. There is really no limit to how complex this can get. Creating such arrangements can be great fun and artistically fulfilling, but some caveats are in order. Managing the melody is really a full time job in Bulgarian music, and playing such orchestral arrangements well is a virtuostic endeavor. This is because your bellows ties together the phrasing of melody, chords and bass notes, so achieving distinction between them is very challenging. Getting some good backup players is really an artistically superior approach to realizing this sort of arrangement (but that, of course, presents its own set of challenges).

I notice the orchestral approach is the one taken almost universally by American students of Bulgarian accordion. In part, this is because the big bass sound is fun, especially in a dance setting. But it is also because it's very difficult to find recordings of unaccompanied Bulgarian accordion to use a guide. Almost all Bulgarian recordings available here feature a double-bass or equivalent, and this gives people the impression that you have to have that kind of bass support to play horos. You don't. The recent rise of wedding band music, which always features a substantial rhythm section, has only reinforced the move toward big bass in Bulgarian music. In contrast, here I will focus in a more circumspect accompaniment style for the accordion that allows the melody to sing a bit more for itself. Some nice recordings of unaccompanied Bulgarian accordion are the following:

A tupan is played with a big stick and little stick. The big stick, most typically, creates a loud low boom, while the little stick creates a high, crisp tock. The accordion equivalents are the tonic bass note (e.g. A) and the chord button that corresponds to the current harmony (e.g. A minor). Depending upon the bass reed combination you choose, you may have more or less contrast between the two. Since the "little stick" is often played very quickly, choose a light reed combination for the chord buttons to insure prompt reed response. The "big stick" reed is used less often so can be thin or thick, low or high. It's fun to experiment by varying the constrast between the big and little stick sounds.

A mark of a good tupanist is the variety of sounds he gets with each stick. Not all big stick hits are the same, nor all little stick. Similarly, not all notes played on bass buttons need be the same. Bass reeds take a while to get going, so a quick depress and release sounds qualitatively different from a long hold. Do not try to change the sounds of your sticks by pulling harder or softer on your bellows. This will disrupt the flow the melody that is tied to the same bellows, and the melody is the important thing. Instead, vary the duration of the reed sounding. You can also experiment with partially depressing the buttons sometimes, which results in a more muted sound.

On the accordion, you have more than one big stick. The tonic bas is your main one, but you should also use other degrees within the present harmony. The 5th degree is the main alternative, but the 3rd degree is also useful. Despite not being "in the chord", the 7th degree often works, especially on pickup beats to the tonic.

You may also use more than one little stick. In a minor harmony (e.g. A minor), the major chord of the 3rd degree can be used to augment the A minor little stick. Both little sticks together form a A minor 7 chord, which is kind of jazzy, but can be appropriate even for old-style tunes if used with disgression.

There are six rhythmic regimes in Bulgarian music:

Asymmetrics are additive rhythms constructed using beat groups of 2 and 3 counts. They are so characteric of Bulgarian music that the term "Bulgarian rhythms" is often used to mean these asymettrics. There are two main division of asymettrics which I will call fast and slow. The fast, more common type, uses building blocks of two or three 16ths, so a 2-count beat takes up an 8th note, and a 3-count beat takes up a dotted 8th.

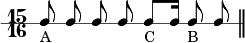

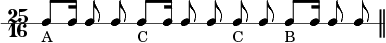

The most common fast asymmetrics are paidushko (5=2+3), ruchenitsa

(7=2+2+3), daichovo (9=2+2+2+3) and gankino/kopanitsa (11=2+2+3+2+2).

There are a handful of other asymmetric combinations that occur with

reasonable frequency, along with an idiosyncratic set of show pieces that

strive to build extremely long patterns of 2s and 3s just for the

hell fun of it. The longest such pattern I've encountered is

45/16.

The first beat of the measure always takes the primary accent. This is unintuitive for most Western students, whose natural tendency is to put the strongest accents on the long (3-count) beats (note 1). Along with the primary accent on beat 1, most rhythms have one or more secondary, and even tertiary, accents. The secondary accent usually occurs somewhere in the latter half of the measure, functioning as a rhythmic pick-up to the primary accent at the start of the next measure. In longer rhythms, tertiary accents are interspersed between the primary and secondary ones to make the rhythmic flow interesting. For some rhythms, there may be some choice is assigning the non-primary accents.

To keep the rhythm flowing in a natural manner, bass side accompaniment for fast asymmetrics should, most of the time, decompose dotted 8ths into an 8th and a 16th. Dotted 8ths in the accompaniment are appropriate at the end of phrases or, occasionally at dramatic points mid-phrase. Mid-phrase usage should be judicious. Too many dotted 8ths will make the beat lurch and lose momentum (note 2). The 16th beats added to the measure in this way never take an accent. Note that decomposing dotted 8ths the opposite way (into a 16th and an 8th) is almost never appropriate, since it obscures the underlying 2-3 asymmetric pattern.

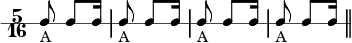

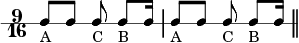

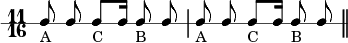

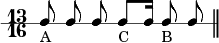

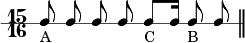

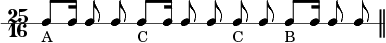

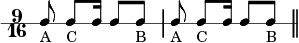

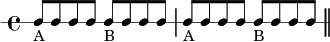

Here is a synopsis of accent patterns in common asymmetrics. "A" denotes the primary, "B" the secondary and "C" the tertiary accents. Bear in mind, these are only the most characteristic accent patterns. A creative accompaniest is constantly making minor variations with the basic stress pattern to maintain listener interest.

| Paidushko |  |

Ruchenitsa |  |

| Chetvorno |  |

Grancharsko |  |

| Daichovo (1) |  |

Daichovo (2) |  |

| Gankino |  |

Petrunino |  |

| Krivo |  |

Buchimish |  |

| Jove |  |

Sedi Donka |  |

Once the beats and accents of a rhythm are defined, forming a bass accompaniment becomes a matter of assigning each beat to a rhythmic tap of your heavy or light "sticks". For starters, let's use two big sticks (tonic and 5th) and one little stick (minor chord). Balance the relative amount of big and little stick accordion to your taste and musical intent. At one extreme, the "feather touch" approach uses mostly little stick, punching the big stick only occasionally. At the other, the "oom-pah" approach alternates tonic and 5th big sticks on strong beats to creating a walking effect, with little sticks filling in-between. In either case, the 5th big stick is usually prepared by recent tonic big stick.

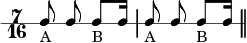

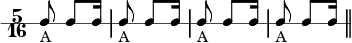

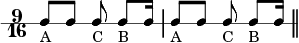

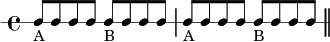

Here are examples of feather touch and oom-pah settings for some common asymmetrics. In between these two extremes, the student will find a wealth of possibility from which he may craft an accompaniment that suits his taste. Examples are set in A minor with 2-3 fingering, assuming a neutral position of the left hand. In feather touch, you may have extended periods on a single chord button. In that case, use alternating fingers (2 and 3) to prevent fatigue and ensure rhythmic accuracy. When harmonies change quickly, the necessary movement of the left hand may necessitate using fingers other than 2 and 3.

| Rhythm | Feather touch | Oom-pah |

|---|---|---|

| Paidushko |  |

|

| Ruchenitsa |  |

|

| Chetvorno |  |

|

| Grancharsko |  |

|

| Daichovo 1 |  |

|

| Daichovo 2 |  |

|

| Gankino |  |

|

| Petrunino |  |

|

| Jove |  |

|

| Sedi Donka |  |

|

Repeating the same sticking pattern each measure is usually a mistake. While the effect is sometimes hypnotic, it more often is turgid and boring. Therefore, consider the phrase, rather than the measure, the unit of accompaniment. Do not feel bound to hitting every accent (not even every primary accent) with a big stick. With the feather touch approach, you may go several measures without a big stick. The goal is to provide interesting rhythmic support for the melody without intruding upon it. You do this by maintaining the internal accent pattern most of the time, but not all the time.

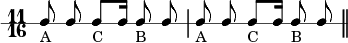

Slow asymmetric rhythms in are those composed of subunits of 2 and 3 eighth notes, in contrast with the subunits of 2 and 3 sixteenth notes that compose fast asymmetrics. This is not merely an notational distinction, because in both cases the underlying melodic pulse is the 16th. There are two common slow asymettrics in the subset of Bulgarian music addressed by this tutorial: elenino (7=2+2+3) and "devetorka" (9=2+2+2+3). I put quotes around devetorka because this term is borrowed from Macedonian music. I'm not aware of a Bulgarian term for this rhythm.

Some asymmetric tunes have melodic action on virtually every 16th note. Most eleninos are this way. Other tunes are mostly 8th notes, with occasional 16th note passages. The underlying 16th note pulse is usually somewhat faster than in fast asymmetrics, so tunes that fill in most of the 16th notes are amoung the most technically difficult of Bulgarian tunes.

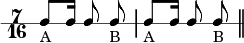

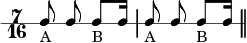

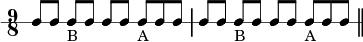

Rhythmic stress is at the start of every 2 or 3 beat group, or internally within the 3-beat groups which can be broken down 1-2 (eighth + quarter) or 2-1 (quarter + eighth), the former being more common. The oom-pah approach is most typical. Here are some typical patterns:

| Elenino |  |

| Devetorka |  |

This tutorial does not cover Macedonian music, which uses a much larger variety of slow asymmetrics than Bulgarian music does, and uses them with more subtlety. Macedonian rhythm is a wonderful and complex subject, but one I'm ignoring for the moment so I can address the present topic. Hopefully, an extension to this tutorial, one covering Macedonian music, will be available at some future point.

There are a variety of simple duple meters in Bulgaria, varying in tempo from the fairly slow and regular (e.g. zborinka) to the very fast and synchopated (e.g. graovsko). They are examined in this section, in order from slowest to fastest. Subsequent sections of this document treat pravos and kjucheks which may also be in simple duple.

Reka & Zborinka: These Dobrudjan dances are slower and heavier than most Bulgarian dances. Bass accompaniment follows the oom-pah pattern with a double bounce of the light stick. Some ideas:

Danetz & Buenek: The women's dances, from Dobruja and Thrace, move somewhat more quickly. You may use the reka/zborinka pattern above, or a simpler, bumping beat illustrated below that is more imitative of the shuffling step of the dancers. The strong beats of this pattern are hit with two together. The light beats with only one:

or alternatively

or alternatively

Trite puti & relatives: These unsynchopated, simple duples come from various parts of Bulgaria and are played primarily with a straight-foward oom-pah. Occasionally, a synchopated pattern similar like Graovsko (see following) may be thrown in for interest.

Graovsko horo: A fast dance from the Shope region normally maintains a synchopated beat of SQSQS where S=slow=quarter note, Q=quick=eighth note. Occasionally it will break into the trite-puti oom-pah beat for a few melodies before settling back into the synchopated one. My usual bass pattern for graovsko is as follows:

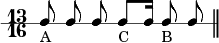

Pravo horo is a mixture simple duple (2/4) and compound duple (6/16). Many songs are simple duple, while the overwhelming majority of instrumental tunes are compound duple. My convention is to notate accordion melodies in 6/16, and handle any simple duple passages with 3:2 rhythmic groupings. Note: this is the opposite convention from that used in most professionally published Bulgarian music (note 3).

Bass side accompaniment for pravo horo may include either compound or simple duple patterns, or a combination thereof. Accompaniments for simple duple melodies may be simple or compound duple. Accompaniments for compound duple melodies are usually compound duple, but not always. Many pravos start slow and build tempo melody by melody. In this case, the accompaniment often begins as simple duple, then switches to compound duple at a dramatic juncture. Even if the head melodies are repeated late the in piece, the accompaniment usually remains compound duple once the switch has been made. Switches between simple and compound duple accompaniment are almost always on phrase boundaries. It's rare to switch back and forth between simple and compound duple accompaniment within a single phrase, even if the melody does so. Therefore, I notate bass patterns that are simple duple in 2/4, and compound duple in 6/16, eliminating the 3:2 rhythmic groupings necessary in melodic notation.

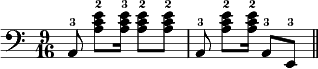

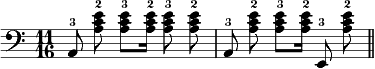

Here is a typical simple duple accompaniment pattern for the song "Pusteno Ludo". This pattern would be appropriate for a relaxed tempo rendition:

Here's the same song with a compound duple accomaniment pattern. This would be appropriate for an up-tempo or lively rendition:

At very fast tempos, pravos are sometimes accompanied by a synchopated simple duple pattern that resembles graovsko (see above). This is really fun!

NOTE: I'm having trouble getting my engraver to represent this correctly. For now, I'm providing the treble and bass lines separately.

Kjucheks are dance melodies in the style of the Bulgarian Roma (aka Gypsies). They are different enough from other Bulgarian dance tunes that they probably belong in a separate tutorial, perhaps the one planned for Macedonian music. However, they are lots of fun, and describing accordion bass accompaniment is relatively simple, so here they are.

Kjucheks come in two basic varieties, those in 2 and those in 9. Accompaniment for those is 2 may be either "swung" (synchopated) or "straight" (unsynchopated). Unlike other Bulgarian music, the accent patterns differ between the melody and accompaniment. The primary melodic accent is on beat 1, while the primary accent for the accompaniment falls somewhere mid-measure. This tension between accent patterns generates much of kjuchek's excitement. Relative to other Bulgarian music, kjuchek places less emphasis on melody and more emphasis in rhythm. This makes it a challenge to play convincing on a solo accordion whose bass side is inevitably less enrapturing than a full rhythm section. However, with crisp execution, a solo accordion kjuchek can be very listenable (and danceable).

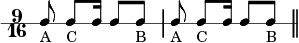

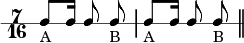

Here are the basic stress patterns for kjuchek. As before, "A" denotes the primary, "B" the secondary, and "C" the tertiary accent.

| Rhythm | Melodic stress | Accompaniment stress |

|---|---|---|

| Kyuchek in 2 (straight) |  |

|

| Kyuchek in 2 (swung) |  |

|

| Kyuchek in 9 |  |

|

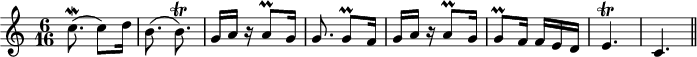

Kjucheks in 2 have simple duple melodies, which I notate in 4/4 with an 8th note pulse. The same set of melodies may be played with either straight or swung accompaniment, but the accompaniment character should remain constant for the duration of the piece. Strive for a pattern that constantly rolls forward. Here's a classic Ibro Lolov tune using simple duple accompaniment:

Here's the same tune with a swung accompaniment. Western students usually need a lot of practice to internalize the stress patterns and maintain them against a melody in an exact way. A crisp attack on the primary accent (the second hit of the measure) is essential.

Kjucheks in 9 decompose 2+2+2+3 and are similar the "devetorka" slow asymmetric, but with a revised stress pattern. An example from Marcus Moskoff:

Bavni pesni, also called slow songs or ballads, are in a rubato, free meter. Bass side accompaniment is done with long sustains of bass notes and/or chord. That's all I'll say about them for now. These songs are worthy of an entire seperate tutorial, one I hope to be able to write in the future.

1: This is especially true for paidushko, probably the hardest of the asymmetrics for Westerners to internalize. The paidushko situation is further confused because there are Macedonian, Romanian and Greek tunes that are structurally similar to paidushko (the Macedonian ones are actually called paidushko) where the accent really is on the long (2nd) beat. This tutorial covers the Bulgarian style however, so primary accent should be on beat 1.

2: Some Balkan performers actually seek out this lurching style (Serbian dance troupes performing "Dances of the Nishava valley", i.e. Bulgarian dances, come immediately to mind). Too often, the resulting lack of rhythmic flow causes performers to compensate by accelerating tempo until all nuance of the melody is lost as well. Barf!

3: In professionally published Bulgarian music, pravo horo is notated in 2/4, with many, many triplet groups to indicate compound duple passages. In addition, there is an idiosyncratic tradition of interpreting certain simple duple notational groups as syncopations in compound duple. I choose to ignore this practice which is obscure and unhelpful for the Western student.

An example of a pravo horo as notated in a Bulgarian publication circa 1969:

How Boris Karlov plays the same piece:

Copyright 2015 Erik Butterworth. All rights reserved.